The Impact of Online Video Learning Activities on Nurses’ and Midwives’ Continuing Professional Education by Anne Wilson in COJ Nursing & Healthcare_journal of nursing and healthcare impact factor

Abstract

Highlights

New knowledge/skills from CPD provides increased confidence to

advocate for best practice; New knowledge/skills result in improved

selfefficacy

enabling better patient care and better patient education; CPD fosters

leadership skills and confidence in demonstrating influence on

health outcomes; The benefit of continuing professional education in

improving competence is identified; The major benefits of online

learning are

convenience and increase accessibility to education

‘This study was conducted to determine the effects of continuing

professional development via online Video Learning Activities for nurses

and

midwives and the perceived contribution to their practice. Change in

knowledge, skills and self-efficacy due to undertaking online Video

Learning

Activities was assessed by two online questionnaires applied through

Survey Monkey TM. Forty-two online learners entered the study and 36

(85.7%)

participants completed the entire protocol. Our study demonstrates

supports the use of innovative Video Learning Activities as part of

continuing

professional education to expand knowledge and skill [1], promote

positive attitudes among nurses and midwives, strengthen patient

provider

relationships, and enhance well-being. Online learning via Video

Learning Activities resulted in the acquisition of new knowledge and/or

skills.

Learning outcomes included change in clinical practice, management

practice, workplace culture, increased awareness of patients’ rights,

and improved

communications with colleagues.

Keyword: Continuing professional education; Video learning activities; Electronic learning; online courses; Survey

Introduction

Nurses and midwives are commonly parents, spouses, and

carers and are working in addition to studying. There is considerable

demand on their time and their responsibilities are high. Hence,

they need flexible study options that are relevant and accessible at

times and in locations that suit them [2]. All these factors impact

on their choice of learning program. Factors nurses and midwives

may consider when choosing the right e-learning provider include;

type of program, type of delivery, the subject material offered [3],

currency of material, how it is offered, when it is offered, where it

is provided, who offers it, who recognises it and being able to move

through it at their own pace.

Online learning as an educational tool for professional learning

and continuing professional development (CPD) has developed

relatively quickly and expansively [3]. Accordingly, the number

of continuing education initiatives that are offered in electronic

formats for the health professions has grown exponentially [4]

and does not appear to be abating [4]. In response to the demand

for time efficiency, and encouraged by intensive competition and

globalization, learning enhanced by information technologies

has gained momentum [5]. This is partially as people’s lives have

become increasingly mobile, complex and multi-dimensional,

online learning has made access to education more accessible,

affordable and desirable. People frequently work in changeable jobs

or situations that require new skills or may cause them to travel

or relocate. Nurses and midwives are a prime example as they are

frequently shift workers, move in a trajectory from novice to expert

and may work in rural or remote areas or be located abroad.

Online learning can be defined as the use of electronic media and

information and communication technologies (ICT) in education

and may be referred to, among other terms, as E-learning. As such

distance education and learning has developed to encompass

sophisticated innovations in content delivery [5,6]. Broadly, it is

delivered digitally through numerous online mechanisms that

include text, audio, images, animation, and streaming video.

Online video tutorials addressing specific knowledge points

are recognised as valuable, flexible, and cost-effective tools that

improve users’ knowledge, skills and self-efficacy [7,8]. Whilst some

consider online learning may never be a complete replacement for

live classroom instruction, there are unique ways to use technology

to assist student learning [6]. Online video tutorials offer targeted

lessons designed with one specific learning goal, as opposed

to presenting learners with broad course instruction or larger

concepts digitally that they must filter through without being able

to ask questions.

The adoption of technology in the provision of education has

been extremely important in providing up-to-date, contemporary

information to meet learners’ needs. The development of the

internet has enabled education providers to modify their approach

and serve students in much better and more creative ways [9].

Online video learning provides learners with increased flexibility

in terms of time and place of study in addition to how much time

they need to spend on a specific topic [9], depending on their prior

knowledge. An advantage [7], when an area of learning difficulty

is encountered, learners are able to view the tutorial material

several times until they fully understand; and, for other points on

which they are familiar, they can skip parts of the tutorial if they

are comfortable with the knowledge point. Thus, video tutorials are

learner controlled, need-based, and task-oriented learning aids.

There is some literature that reports the effect of Internetdelivered

continuing education on changes in knowledge, skills, and

self-efficacy on health professional education (Martin, Bruskiewitz,

& Chewning, 2010). Self-efficacy and perceived ability to counsel

patients on healthy behaviour has been known to improve

significantly after CPE [10]. Nurses, midwives and other regulated

health professionals must be confident that the e-education they

access is current, relevant, and of a high standard, facilitating

their professional and legislative requirements. Registered health

professionals such as nurses are required to undertake CPD to

maintain their registration to practice and need education that is

theoretical, informed, rigorous, and meets registration standards.

A wide variety of different types of online education services

are available and as they are continuously evolving, it is crucial

that their effectiveness for the learners’ needs and for the safety of

the community that sustainable and quality services are ensured.

If optimum knowledge transfer to learners is to occur, monitoring

performance and outcomes of education programs requires

evaluations and appraisals that keep pace with the rapid changes in

learning technology and learners’ needs. This is also an important

requirement for education providers seeking accreditation of their

programs [9]. The purpose of this study was to determine the

effects of online video learning activities in delivering educational

activities that improved learners’ self-efficacy, knowledge, skills

and that this new knowledge was, in some way, translated into

practice.

Methods

A nursing education and technology company based in North

Melbourne Australia, and specializing in web-based technological

applications that help nurses with continuing professional

development, commissioned an independent consultant to

evaluate users’ perceived effectiveness of VLAs provided by its

online ‘Learning Centre’ on their professional development.

Effectiveness is self-reported to indicate effects on learners’ selfefficacy,

knowledge and translation of knowledge into practice.

Permission to conduct the study was provided by the Belberry

Human Research Ethics Committee. A descriptive exploratory

design involving two phases of data collection via two online surveys

was undertaken. Both numerical and text data were collected and

statistical and text analyses applied.

Theoretical framework

A descriptive, exploratory survey design was used to identify

users’ perceptions of the educational benefit of their learning

experience and to indicate its effects on processes and outcomes

of clinical care. The survey tool utilised a mixed method evaluation

approach of quantitative and qualitative questions. Questionnaires

were formulated based on studies retrieved from the reviewed

literature, the research question and the knowledge of the research

team. In particular, the data collections tools were informed

from those described by Carlson [11] and England [7]. Although

published instruments had been used, both questionnaires were

pre-tested prior to their application to ensure validity and reliability

in the existing population.

Measures

Questionnaire one sought personal and professional

information, how participants anticipated translating their new

knowledge and/or skills into practice, and the impact of VLAs on

knowledge, attitudes and skills. Questionnaire two investigated

whether the VLA resulted in new knowledge and/or skills and if this

had an impact on certain areas of practice; and how respondents

translated their new knowledge and/or skills into practice. Openended

response opportunities invited participants’ to elaborate on

their responses after most questions in both questionnaires.

Sample

Online subscribers who completed a VLA through the ‘Learning

Centre’ during the data collection period and who indicated in

their evaluation that they planned to use their learning to make

improvements to their practice were identified and invited to

participate in the study. A letter detailing the purpose, intentions,

and requirements of participation and link to the first questionnaire

was emailed by the investigator to identified participants. At the end

of the first questionnaire, participants were asked to provide their

email address if they consented to being contacted to participate in

the second questionnaire. The setting for the study was in the online

environment at personal computers of participants’ choosing.

Procedures

The two questionnaires were applied online through Survey

Monkey TM two months apart. Questionnaire one opened on

15th May 2014. The participant information sheet and a link

to the questionnaire on Survey Monkey TM were sent to online

subscribers who indicated that they would use their learning from a VLA

completed during 14th April 2014 to 13th May 2014 to make

improvements to their practice. Participants were given three

weeks to complete the survey and a reminder email was sent at the

end of the second week.

The link to the second questionnaire was sent via email to 36

out of 42 participants who responded to the first questionnaire

and provided their consent and email addresses to be contacted.

This email was sent on the 15thAugust 2014 and participants were

advised they would have three weeks to complete the survey. A

reminder email was sent one week before the due date.

Data Analysis

Participants’ responses were analysed with descriptive

(summative, frequency and percentage) statistics, and reported

in tables, charts and free text. Data were imported from Survey

Monkey TM for management in Excel TM and checked for accuracy

and quality. Descriptive statistics were used to characterise the

sample. Liker response data was analysed to report the most

frequent response with the spread of responses displayed in

charts/graphics.

Textual data were entered into a word document for each

question. A content analysis was then conducted on the data

with the responses grouped according to the meaning, or overall

sentiment, of the response [12]. Where some responses provided

more than one meaning, the response was counted towards each.

Results

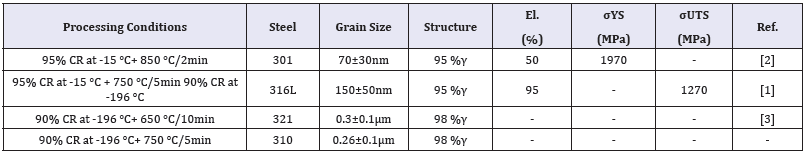

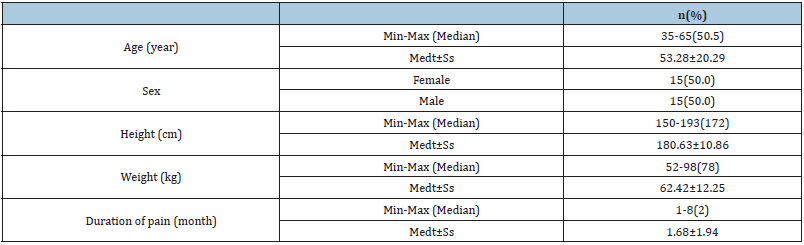

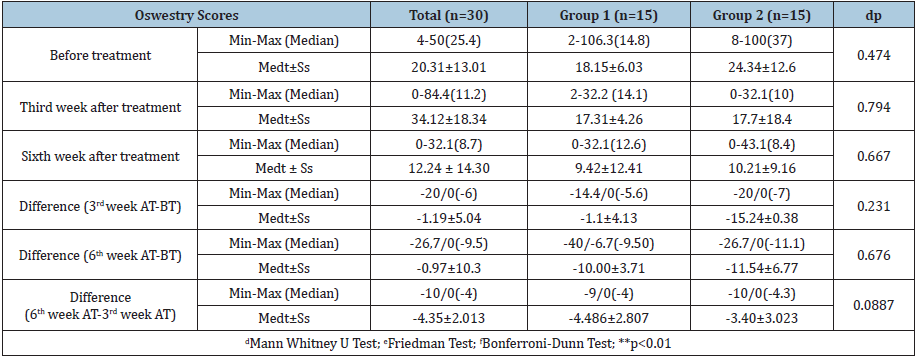

Characteristics of the sample

A total of 42 online learners entered the study and 36 (85.7%)

participants completed the entire protocol. The typical participant

was a 41 to 59 year old female, working in acute care with over

30 years nursing experience and employed part-time or casual

(Table 1). Less than half the participants (42.9%) indicated they

had post-graduate qualifications. The majority of participants

(88%) lived in one of the Eastern States of Australia and 69% were

born in Australia. Two respondents (4.8%) identified as being of

either Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander descent. Participants’

experience in nursing/midwifery ranged from 2-50 years.

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of participants.

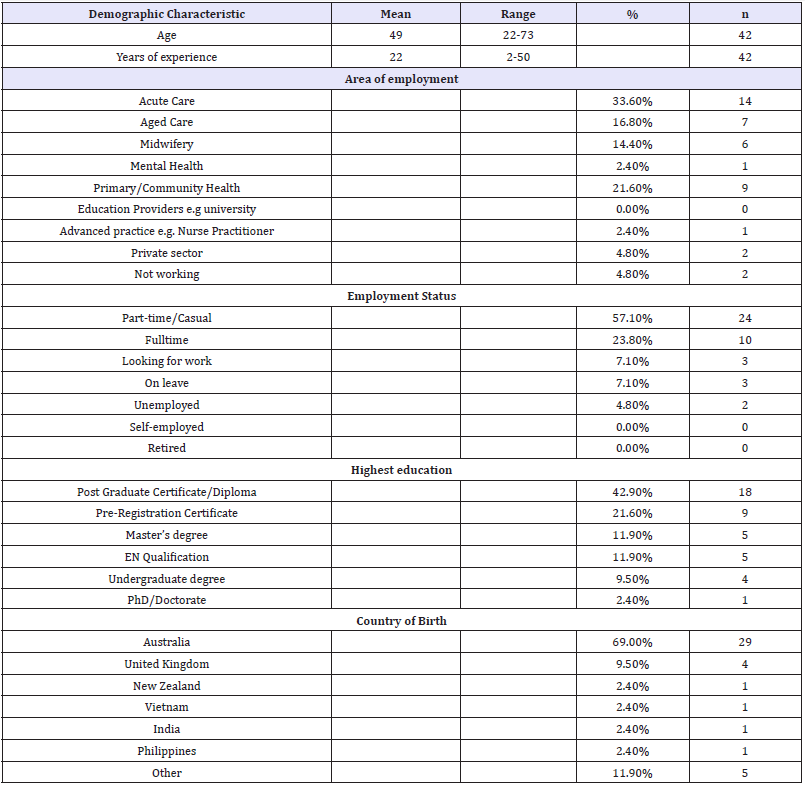

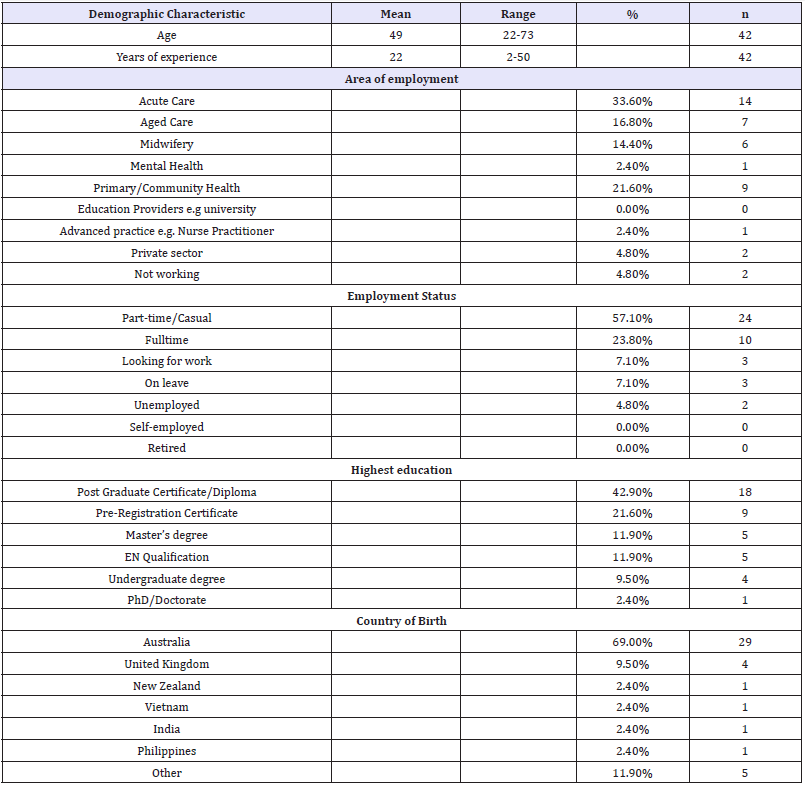

Motives for continuing professional education

The three most common reasons identified for undertaking

CPD were: maintaining nursing/midwifery registration (n=37;

88.1%), keeping up-to-date (n=34; 81%) and because they liked

learning (n=25; 59.5%) (Table 2). None of the participants chose

job promotion as a reason for undertaking CPD.

Table 2: Reasons for undertaking CPD (multiple options).

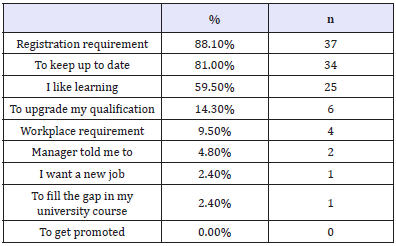

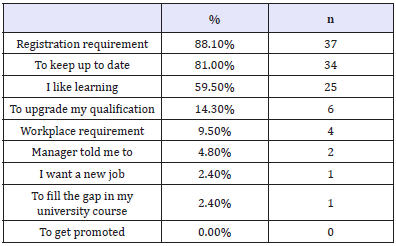

Continuing Professional Development via VLAs was mainly

preferred for its flexibility (n=38; 90.5%), 24 hour availability (n=34;

81%); and personalised pace of study (n=30; 71.4%). The currency

of the material delivered was rated 5th (n=19; 45.2%) in the nine

options provided (Table 3). Additional benefits of learning via VLAs

as stated by participants included: lack of education availability in

rural areas and being able to absorb more information.

Table 3: Advantages of Video Learning Activities (multiple options).

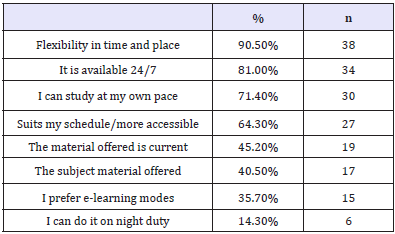

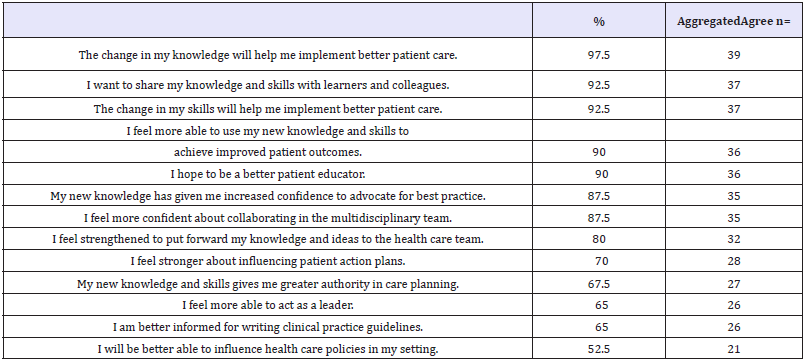

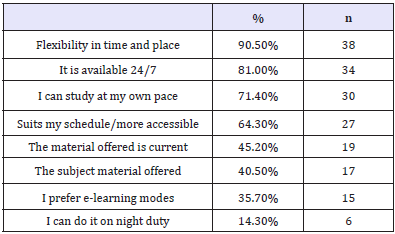

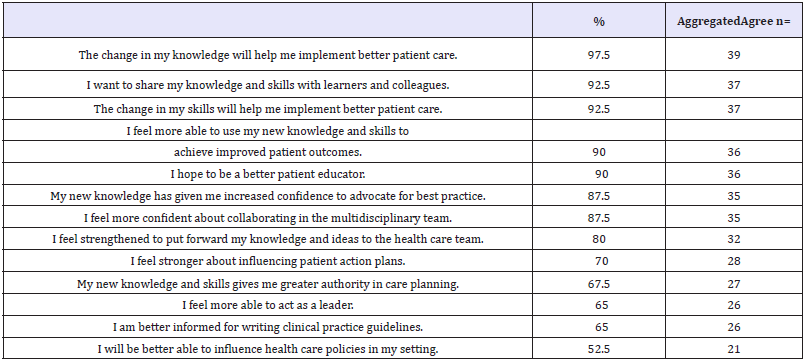

Influence of the chosen educational intervention

Forty (n=40; 95%) participants positively scored the impact

that their acquired knowledge from the VLAs chosen. Responses

were aggregated to reflect the majority’s responses in the

following categories: agree; neutral; disagree. Implementing better

patient care, sharing knowledge and skills and improving patient

outcomes had the strongest agreement about how new knowledge

had influenced participants (Table 4). Participants were unsure

they would be more able to influence healthcare (n=21; 52.5%),

implement a new or changed model of care (n=18; 45%); or present

a new or changed model of care at a conference (n=18; 45%).

Nearly half of the participants disagreed they hoped to publish a

new or changed model of care in a health journal (n=19; 47.5%).

Table 4: Influence from new knowledge.

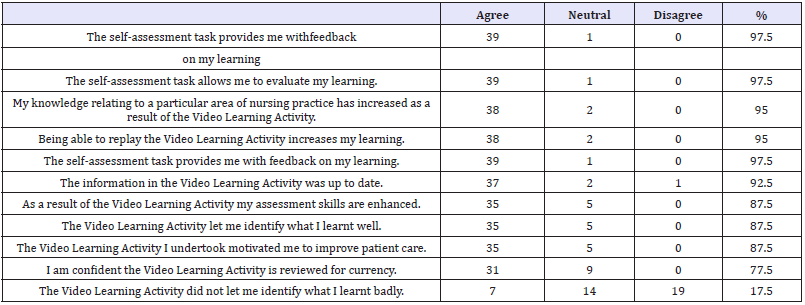

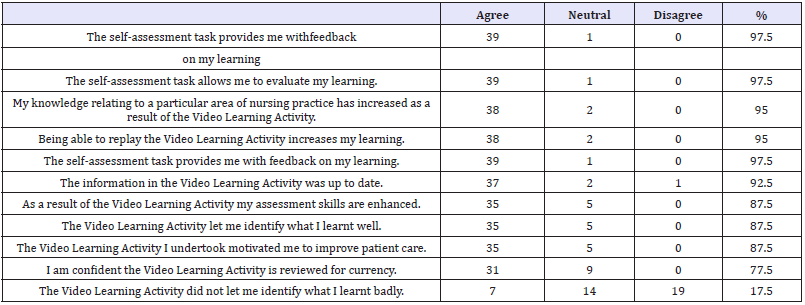

Augmented learning and self-assessment, increased knowledge

and enhanced nursing/midwifery skills were reportedly achieved

from the VLAs (87.5-97.5%) (Table 5). Most respondents found

the learning beneficial, motivational and empowering (87.5%) and

the VLAs allowed learners to identify what they had not learnt well

(47.5%).

Table 5: VLAs impact on Knowledge, attitudes and skills (n=40).

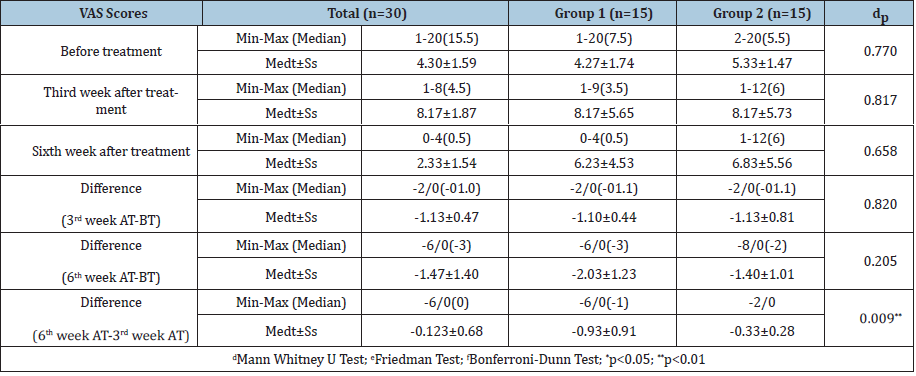

Effect of participating in the VLA/CPD

All respondents agreed/strongly agreed that participation

in the VLAs resulted in new knowledge/skills and that with new

knowledge they had increased confidence to advocate for best

practice. Thirteen (93%) reported that new knowledge and skills

enabled them to provide better patient care and 11 (78%) were

able to be a better patient educator. Others were able to contribute

to improved patient outcomes and contribute more strongly in the

health team (n=10; 71%). Reportedly, new knowledge and skills

contributed to a change in others’ and self-perception (n=8; 57%).

To be a leader and demonstrate influence were positively ranked

by 50% of respondents although 64.2% were unsure whether they

were better placed to gain a leadership position. In contrast to the

increase in clinical skills, scholarly activities such as publication and

presentation of new models of care were not considered achievable

(Table 6).

Discussion

The reported study evaluated users’ learning experience,

perceptions and outcomes from studying via online video learning

activities. Significantly, respondents found that participation in the

VLAs resulted in new knowledge/skills that resulted in improved

self-efficacy and enabled them to provide better patient care and be

a better patient educator. Consequently, this reportedly contributed

to improved patient health outcomes and stronger contribution

and influence in the multidisciplinary health team. The benefit

of continuing professional education in improving competence

has been identified [13]. Similar to findings from other studies of

participants’ perception of CPE, participants generally perceived

CPE as valuable and worthwhile and participated because it is

mandatory and helps them to retain their jobs [14].

Generally, participants were shown to be experienced, busy

professionals with a range of personal responsibilities. The majority

of respondents lived in three Australian states and none were

from overseas. Some respondents were born in countries other

than Australia and spoke a variety of languages including Spanish,

Mandarin, Hakka, Serbo-Croatian, Bosnian, Vietnamese, Tagalog

and Afrikaans. VLAs were mainly preferred for their flexibility,

availability; and personalised pace of studying. Participants were

self-directed with studying and self-identified their study needs.

Health professionals a positive attitude towards professional

development is recognised [13].

The reported demographics of the study population show the

aged care sector was the third most commonly reported area of

employment and acute care the first. As stated in the Australian

Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) report, in 2013, the work

setting of employed nurses and midwives with the highest full

time equivalent (FTE) rate was hospitals (excluding outpatients)

(Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2013).

The gender of the research participants reflects the gender

proportions of the nursing and midwifery workforce in Australia. In

2013, 10.4% of nurses and midwives working in Australia identified

as male (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2013), a similar

proportion to those in the study (male 9.5%).

Participants in this study met the national Australian averages in

relation to age, experience, gender and working hours. Similar to the

respondents in this study (57.1%), data collected by the Australian

Health Practitioner Registration Authority (AHPRA) in 2013 also

shows that the majority of employed nurses and midwives (46.8%)

work part time [15]. The desire for fulltime employment did not

appear to be an incentive to study as the large majority (88.1%)

of respondents indicated CPD was a re-registration requirement

in Australia and consequently the primary reason for undertaking

CPD. Disappointingly, the need for further education for promotion

or other employment was not required, although this is not the

case in some professions where CPEs become a valued credential

that helps obtaining and keeping desirable positions, as well as

advancement to the next level in careers [16].

Congruent with data collected by AHPRA in 2013 which

shows that the majority of nurses were in the 50-54 year age

bracket, followed by 55-59 years, and 45-49 years, the majority

of respondents (61.4%) fell between the ages of 41 and 59 years

(Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2013). Ageing of the

nursing workforce has been cited as a reason for the workforce

shortages in nursing in Australia [15]. Accordingly, just under half

of the respondents (42.8%) reported significant nursing/midwifery

experience of over 30 years, ranging up to 50 years. Additionally,

high responsibility levels including work plus study plus carer

responsibilities may be a factor affecting nearly three quarters of

the participants who reported not working fulltime.

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, in mid-2011

there was 27% of the total population born outside of Australia

[1]. In accord, 31% of respondents were born outside Australia.

This population consisted of people who were born in UK, NZ,

Vietnam, India Philippines, Malaysia, El Salvador, Denmark, former

Yugoslavia and South-Africa, showing Australia’s multi-culturism

and therefore need to provide education that meets the needs of

nurses and midwives educated outside Australia.

The major benefits of online learning are known to include

convenience and increase accessibility to education. Respondents

reported that Video Learning Activities were mainly preferred over

classroom presentations for their flexibility, 24-hour availability,

and personalised pace of study. Preference due to the currency of

the material delivered was rated fifth of the nine options provided.

Additionally, respondents living in a rural area indicated there was

limited education available to them and the VLAs allowed nurses

and midwives working in rural and remote areas to undertake CPD

more readily and with greater flexibility. Geographic isolation and

poor technological and telecommunications infrastructure and

unemployment are identified as key barriers to CPE delivery and

access [13,14].

The majority of respondents reported they had online learning

experience with other education providers but rated the learning

impact of VLAs higher. Respondents reported that their previous

online learning experience had resulted significantly in a change

in their knowledge and skills, a change in their self-confidence and

change in their professional collaboration. This correlated with

the outcomes of the VLAs where all respondents agreed/strongly

agreed that participation in the VLA resulted in new knowledge/

skills and that with new knowledge they had increased confidence

to advocate for best practice. Examination of the influence of

interactive video on learning outcome and learner satisfaction in

e-learning environments has shown that students in the e-learning

environment that provided interactive video achieved significantly

better learning performance and a higher level of learner

satisfaction than those in other settings [5].

New knowledge and skills enables nurses to provide better

patient care and be able to be a better patient educator, to contribute

to improved patient outcomes and contribute more strongly in

the health care team. Interestingly respondents were unsure they

would be more able to influence healthcare, implement a new or

changed model of care or present a new or changed model of care

at a conference. Potentially, targeted education activities could

address this lack of confidence or knowledge.

VLAs were considered to be desirable and beneficial to

professional development. The majority of respondents did not

prefer classroom teaching over VLAs. Augmented learning and

self-assessment, increased knowledge and enhanced nursing skills

were reportedly achieved from the VLAs. Most respondents found

the learning useful and empowering (87.5%) and the VLAs allowed

learners to identify what they have not learnt well (47.5%).

Limitations

The response rate to the study in general was lower than

hoped and potentially limited the study and the sample size was

too small to allow for meaningful statistics. The response rate in

survey research is known to be problematical and a meaningful

reward for participation such as CPD points may have increased

participation. A larger sample with more diversity would have

benefited our results as may have the inclusion of learners studying

from international settings and experiencing different occurrences.

Nevertheless, all respondents completed the questionnaire in

enough detail for them to be analysed and contribute to answering

the research questions and the low response rate does not appear

to be impacted by non-response bias in a major way [17]. Due to the

small number of participants data is not representative of all nurses

and midwives.

For consistency and ability to compare and contrast data, using

the AIHW style of requesting specific information for principal

area of main job and work setting of main job reporting as basis

for asking area of employment would have been beneficial. The

majority of respondents lived in three of Australia’s eastern States

and unknowingly the survey did not allow for overseas postcodes

to be entered. A larger number of participants from rural areas of

Central Australia and Western Australia and overseas may have

provided different personal and professional demographics and a

different reflection of needs and perspectives.

Conclusion

This descriptive research study was conducted as an internal

service provision review and to determine the impact of CPD via online Video Learning Activities and the contribution made

to learners’ professional practice. The study has contributed to

the scarce literature about VLAs for CPD provided by private

enterprise and to closing the gap in what is known about e-service

usage for CPD by exploring learners’ experiences and learning

outcomes of VLAs via online learning. The findings suggest that it

may be important to integrate interactive instructional video into

e-learning systems.

Participants generally perceived CPE as valuable and

worthwhile and participated because it is mandatory and helps

them to retain their jobs. A second main finding from this study

is that nurses and midwives who undertook VLAs were confident

they had gained new knowledge and skills, which could be applied

to their practice. However, it is difficult to quantify or measure the

direct impact of this new knowledge and skills on actual practice.

This is because nurses and midwives may perceive they have applied

their new knowledge and skills but this may not have translated

into improved practice. Therefore, rather than only evaluate online

learning per se, it is important that education providers evaluate

the effectiveness in terms of knowledge transference to practice.

In addition, providers need to ensure the technology used and the

rigor of the education meets the needs of contemporary nurses and

midwives.

The project trialled a methodology that may be applied by other

education providers to assess the delivery of educational activities

that improve learners’ self-efficacy, knowledge and translation

of new knowledge and skills into practice. Challenges identified

included gaps in rural education that could be met by e-learning

and the need to continue to develop online learning opportunities.

Education providers need to continue to provide topics that address

the learning needs of nurses and midwives through a variety of

strategies. Mitchell [18] insists that the values and beliefs following

post registration education and practice decree that CPE must be

tailored to the needs of the individual and relevant to the practice

environment [18,19].

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (2013) Migration Australia, 2011-12

and 2012-13. Estimated resident population, Country of birth, State/

territory, Age and sex.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2013) Nursing and midwifery

workforce

- Gikandi JW, Morrow D, Davis NE (2011) Online formative assessment

in higher education: A review of the literature. Computers & Education

57(4): 2333-2351.

- Cobb SC (2004) Internet continuing education for health care

professionals: An integrative review. J Contin Educ Health Prof 24(3):

171-180.

- Zhang D, Zhou L, Briggs RO, Nunamaker JF (2006) Instructional video

in e-learning: Assessing the impact of interactive video on learning

effectiveness. Information & management 43(1): 15-27.

- He Y, Swenson S, Lents N (2012) Online Video Tutorials Increase

Learning of Difficult Concepts in an Undergraduate Analytical Chemistry

Course. Journal of Chemical Education 89(9): 1128-1132.

- Engelland BT, Hopkins C, Workman L, Singh M (1998) Service quality

and repeat usage: a case of rising expectations. Journal of Marketing

Management 8(2): 1-6.

- Stark CM, Graham Kiefer ML, Devine CM, Dollahite JS, Olson CM (2011)

Online Course Increases Nutrition Professionals’ Knowledge, Skills,

and Self-Efficacy in Using an Ecological Approach to Prevent Childhood

Obesity. J Nutr Educ Behav 43(5): 316-322.

- Ng KS, Abd R, Muhudin A (2014) E-Service Quality in Higher Education

and Frequency of Use of the Service. International Education Studies

7(3): 1-10.

- Martin BA, Bruskiewitz RH, Chewning BA (2010) Effect of a tobacco

cessation continuing professional education program on pharmacists’

confidence, skills, and practice-change behaviors. J Am Pharm Assoc

50(1): 9-16.

- Carlson J, OCass A (2010) Exploring the relationships between e-service

quality, satisfaction, attitudes and behaviours in content-driven e-service

web sites. The Journal of Services Marketing 24(2): 112-127.

- Pope C, Mays N, Popay J (2007) Synthesising Qualitative and Quantitative

Health Research: A Guide to Methods. Maidenhead: Open University

Press, UK.

- Keim KS, Gates GE, Johnson CA (2001) Dietetics professionals have

a positive perception of professional development.J Am Diet Assoc

101(7): 820-824.

- Curran VR, Fleet L, Kirby F (2006) Factors influencing rural health care

professionals’ access to continuing professional education. Aust J Rural

Health 14(2): 51-55.

- Graham EM, Duffield C (2010) An ageing nursing workforce. Aust Health

Rev 34(1): 44-48.

- Linney B J (1998) Why become a certified physician executive? Physician

exec 24(2): 50-52.

- Rok Seon Choung, G Richard Locke III, Cathy D Schleck, Jeanette Y

Ziegenfuss, Timothy J Beebe, Alan R Zinsmeister, et al. (2013) A low

response rate does not necessarily indicate non-response bias n

gastroenterology survey research: a population-based study. Journal of

Public Health 21(1): 87-95.

- Mitchell M (1997) The continuing professional education needs of

midwives. Nurse Educ Today 17(5): 394-402.

- Nsemo AD, John ME, Etifit RE, Mgbekem, MA, Oyira EJ (2013) Clinical

nurses’ perception of continuing professional education as a tool for

quality service delivery in public hospitals Calabar, Cross River State,

Nigeria. Nurse Educ Pract 13(4): 328-334.

For more articles in journal of nursing and healthcare impact factor