The Impact of Online Video Learning Activities on Nurses’ and Midwives’ Continuing Professional Education by Anne Wilson in COJ Nursing & Healthcare_journal of nursing and healthcare impact factor

Abstract

Highlights

New knowledge/skills from CPD provides increased confidence to advocate for best practice; New knowledge/skills result in improved selfefficacy enabling better patient care and better patient education; CPD fosters leadership skills and confidence in demonstrating influence on health outcomes; The benefit of continuing professional education in improving competence is identified; The major benefits of online learning are convenience and increase accessibility to education

‘This study was conducted to determine the effects of continuing professional development via online Video Learning Activities for nurses and midwives and the perceived contribution to their practice. Change in knowledge, skills and self-efficacy due to undertaking online Video Learning Activities was assessed by two online questionnaires applied through Survey Monkey TM. Forty-two online learners entered the study and 36 (85.7%) participants completed the entire protocol. Our study demonstrates supports the use of innovative Video Learning Activities as part of continuing professional education to expand knowledge and skill [1], promote positive attitudes among nurses and midwives, strengthen patient provider relationships, and enhance well-being. Online learning via Video Learning Activities resulted in the acquisition of new knowledge and/or skills. Learning outcomes included change in clinical practice, management practice, workplace culture, increased awareness of patients’ rights, and improved communications with colleagues.

Keyword: Continuing professional education; Video learning activities; Electronic learning; online courses; Survey

Introduction

Nurses and midwives are commonly parents, spouses, and carers and are working in addition to studying. There is considerable demand on their time and their responsibilities are high. Hence, they need flexible study options that are relevant and accessible at times and in locations that suit them [2]. All these factors impact on their choice of learning program. Factors nurses and midwives may consider when choosing the right e-learning provider include; type of program, type of delivery, the subject material offered [3], currency of material, how it is offered, when it is offered, where it is provided, who offers it, who recognises it and being able to move through it at their own pace.

Online learning as an educational tool for professional learning and continuing professional development (CPD) has developed relatively quickly and expansively [3]. Accordingly, the number of continuing education initiatives that are offered in electronic formats for the health professions has grown exponentially [4] and does not appear to be abating [4]. In response to the demand for time efficiency, and encouraged by intensive competition and globalization, learning enhanced by information technologies has gained momentum [5]. This is partially as people’s lives have become increasingly mobile, complex and multi-dimensional, online learning has made access to education more accessible, affordable and desirable. People frequently work in changeable jobs or situations that require new skills or may cause them to travel or relocate. Nurses and midwives are a prime example as they are frequently shift workers, move in a trajectory from novice to expert and may work in rural or remote areas or be located abroad.

Online learning can be defined as the use of electronic media and information and communication technologies (ICT) in education and may be referred to, among other terms, as E-learning. As such distance education and learning has developed to encompass sophisticated innovations in content delivery [5,6]. Broadly, it is delivered digitally through numerous online mechanisms that include text, audio, images, animation, and streaming video.

Online video tutorials addressing specific knowledge points are recognised as valuable, flexible, and cost-effective tools that improve users’ knowledge, skills and self-efficacy [7,8]. Whilst some consider online learning may never be a complete replacement for live classroom instruction, there are unique ways to use technology to assist student learning [6]. Online video tutorials offer targeted lessons designed with one specific learning goal, as opposed to presenting learners with broad course instruction or larger concepts digitally that they must filter through without being able to ask questions.

The adoption of technology in the provision of education has been extremely important in providing up-to-date, contemporary information to meet learners’ needs. The development of the internet has enabled education providers to modify their approach and serve students in much better and more creative ways [9]. Online video learning provides learners with increased flexibility in terms of time and place of study in addition to how much time they need to spend on a specific topic [9], depending on their prior knowledge. An advantage [7], when an area of learning difficulty is encountered, learners are able to view the tutorial material several times until they fully understand; and, for other points on which they are familiar, they can skip parts of the tutorial if they are comfortable with the knowledge point. Thus, video tutorials are learner controlled, need-based, and task-oriented learning aids.

There is some literature that reports the effect of Internetdelivered continuing education on changes in knowledge, skills, and self-efficacy on health professional education (Martin, Bruskiewitz, & Chewning, 2010). Self-efficacy and perceived ability to counsel patients on healthy behaviour has been known to improve significantly after CPE [10]. Nurses, midwives and other regulated health professionals must be confident that the e-education they access is current, relevant, and of a high standard, facilitating their professional and legislative requirements. Registered health professionals such as nurses are required to undertake CPD to maintain their registration to practice and need education that is theoretical, informed, rigorous, and meets registration standards.

A wide variety of different types of online education services are available and as they are continuously evolving, it is crucial that their effectiveness for the learners’ needs and for the safety of the community that sustainable and quality services are ensured. If optimum knowledge transfer to learners is to occur, monitoring performance and outcomes of education programs requires evaluations and appraisals that keep pace with the rapid changes in learning technology and learners’ needs. This is also an important requirement for education providers seeking accreditation of their programs [9]. The purpose of this study was to determine the effects of online video learning activities in delivering educational activities that improved learners’ self-efficacy, knowledge, skills and that this new knowledge was, in some way, translated into practice.

Methods

A nursing education and technology company based in North Melbourne Australia, and specializing in web-based technological applications that help nurses with continuing professional development, commissioned an independent consultant to evaluate users’ perceived effectiveness of VLAs provided by its online ‘Learning Centre’ on their professional development. Effectiveness is self-reported to indicate effects on learners’ selfefficacy, knowledge and translation of knowledge into practice.

Permission to conduct the study was provided by the Belberry Human Research Ethics Committee. A descriptive exploratory design involving two phases of data collection via two online surveys was undertaken. Both numerical and text data were collected and statistical and text analyses applied.

Theoretical framework

A descriptive, exploratory survey design was used to identify users’ perceptions of the educational benefit of their learning experience and to indicate its effects on processes and outcomes of clinical care. The survey tool utilised a mixed method evaluation approach of quantitative and qualitative questions. Questionnaires were formulated based on studies retrieved from the reviewed literature, the research question and the knowledge of the research team. In particular, the data collections tools were informed from those described by Carlson [11] and England [7]. Although published instruments had been used, both questionnaires were pre-tested prior to their application to ensure validity and reliability in the existing population.

Measures

Questionnaire one sought personal and professional information, how participants anticipated translating their new knowledge and/or skills into practice, and the impact of VLAs on knowledge, attitudes and skills. Questionnaire two investigated whether the VLA resulted in new knowledge and/or skills and if this had an impact on certain areas of practice; and how respondents translated their new knowledge and/or skills into practice. Openended response opportunities invited participants’ to elaborate on their responses after most questions in both questionnaires.

Sample

Online subscribers who completed a VLA through the ‘Learning Centre’ during the data collection period and who indicated in their evaluation that they planned to use their learning to make improvements to their practice were identified and invited to participate in the study. A letter detailing the purpose, intentions, and requirements of participation and link to the first questionnaire was emailed by the investigator to identified participants. At the end of the first questionnaire, participants were asked to provide their email address if they consented to being contacted to participate in the second questionnaire. The setting for the study was in the online environment at personal computers of participants’ choosing.

Procedures

The two questionnaires were applied online through Survey Monkey TM two months apart. Questionnaire one opened on 15th May 2014. The participant information sheet and a link to the questionnaire on Survey Monkey TM were sent to online subscribers who indicated that they would use their learning from a VLA completed during 14th April 2014 to 13th May 2014 to make improvements to their practice. Participants were given three weeks to complete the survey and a reminder email was sent at the end of the second week.

The link to the second questionnaire was sent via email to 36 out of 42 participants who responded to the first questionnaire and provided their consent and email addresses to be contacted. This email was sent on the 15thAugust 2014 and participants were advised they would have three weeks to complete the survey. A reminder email was sent one week before the due date.

Data Analysis

Participants’ responses were analysed with descriptive (summative, frequency and percentage) statistics, and reported in tables, charts and free text. Data were imported from Survey Monkey TM for management in Excel TM and checked for accuracy and quality. Descriptive statistics were used to characterise the sample. Liker response data was analysed to report the most frequent response with the spread of responses displayed in charts/graphics.

Textual data were entered into a word document for each question. A content analysis was then conducted on the data with the responses grouped according to the meaning, or overall sentiment, of the response [12]. Where some responses provided more than one meaning, the response was counted towards each.

Results

Characteristics of the sample

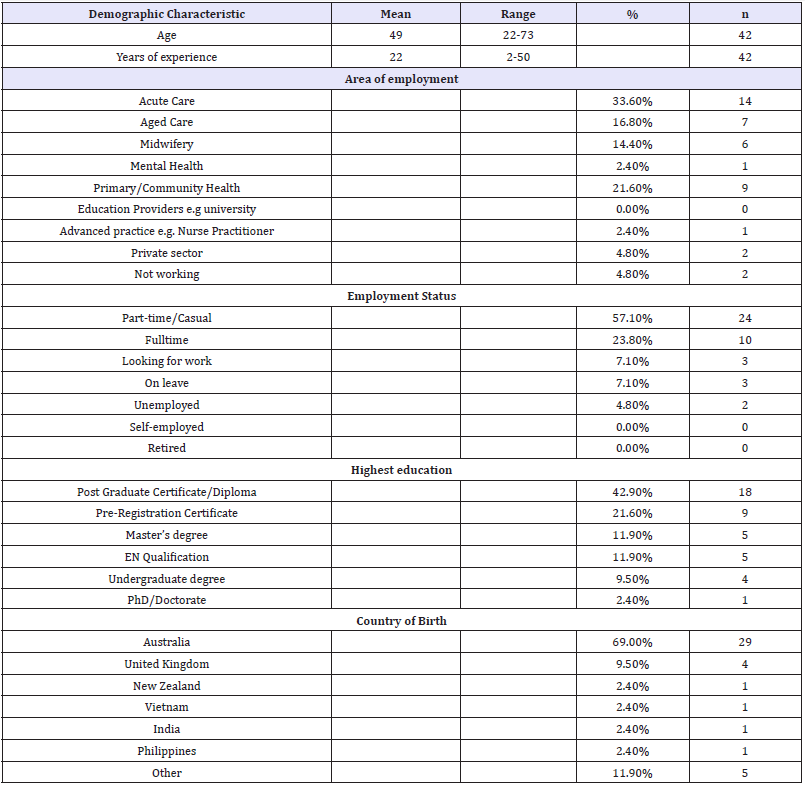

A total of 42 online learners entered the study and 36 (85.7%) participants completed the entire protocol. The typical participant was a 41 to 59 year old female, working in acute care with over 30 years nursing experience and employed part-time or casual (Table 1). Less than half the participants (42.9%) indicated they had post-graduate qualifications. The majority of participants (88%) lived in one of the Eastern States of Australia and 69% were born in Australia. Two respondents (4.8%) identified as being of either Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander descent. Participants’ experience in nursing/midwifery ranged from 2-50 years.

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of participants.

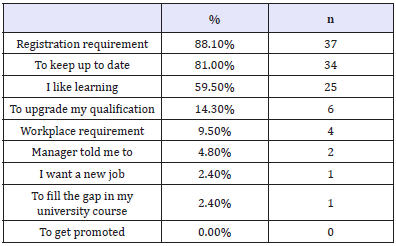

Motives for continuing professional education

The three most common reasons identified for undertaking CPD were: maintaining nursing/midwifery registration (n=37; 88.1%), keeping up-to-date (n=34; 81%) and because they liked learning (n=25; 59.5%) (Table 2). None of the participants chose job promotion as a reason for undertaking CPD.

Table 2: Reasons for undertaking CPD (multiple options).

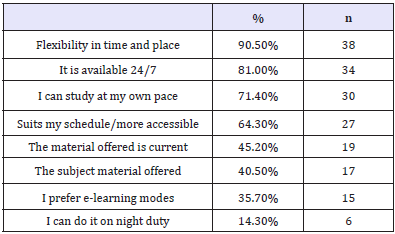

Continuing Professional Development via VLAs was mainly preferred for its flexibility (n=38; 90.5%), 24 hour availability (n=34; 81%); and personalised pace of study (n=30; 71.4%). The currency of the material delivered was rated 5th (n=19; 45.2%) in the nine options provided (Table 3). Additional benefits of learning via VLAs as stated by participants included: lack of education availability in rural areas and being able to absorb more information.

Table 3: Advantages of Video Learning Activities (multiple options).

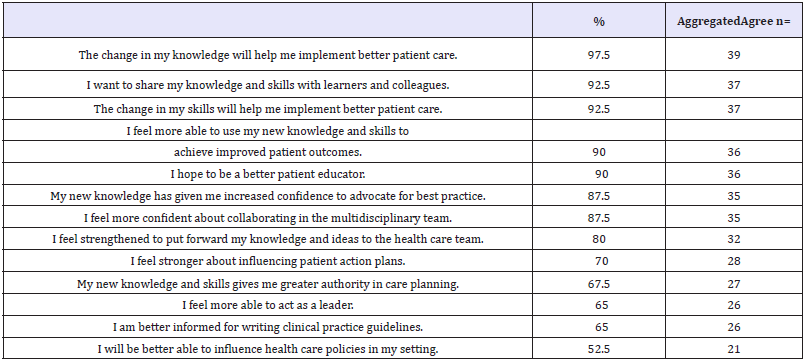

Influence of the chosen educational intervention

Forty (n=40; 95%) participants positively scored the impact that their acquired knowledge from the VLAs chosen. Responses were aggregated to reflect the majority’s responses in the following categories: agree; neutral; disagree. Implementing better patient care, sharing knowledge and skills and improving patient outcomes had the strongest agreement about how new knowledge had influenced participants (Table 4). Participants were unsure they would be more able to influence healthcare (n=21; 52.5%), implement a new or changed model of care (n=18; 45%); or present a new or changed model of care at a conference (n=18; 45%). Nearly half of the participants disagreed they hoped to publish a new or changed model of care in a health journal (n=19; 47.5%).

Table 4: Influence from new knowledge.

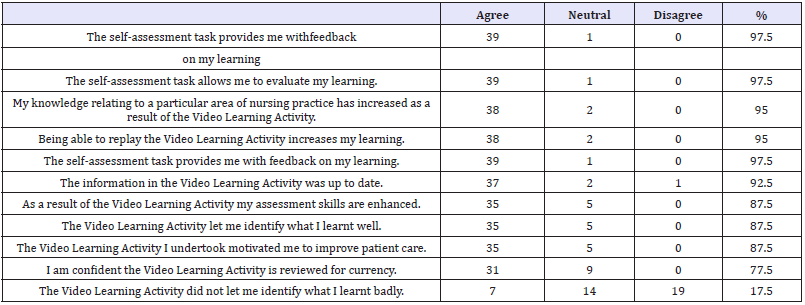

Augmented learning and self-assessment, increased knowledge and enhanced nursing/midwifery skills were reportedly achieved from the VLAs (87.5-97.5%) (Table 5). Most respondents found the learning beneficial, motivational and empowering (87.5%) and the VLAs allowed learners to identify what they had not learnt well (47.5%).

Table 5: VLAs impact on Knowledge, attitudes and skills (n=40).

Effect of participating in the VLA/CPD

All respondents agreed/strongly agreed that participation in the VLAs resulted in new knowledge/skills and that with new knowledge they had increased confidence to advocate for best practice. Thirteen (93%) reported that new knowledge and skills enabled them to provide better patient care and 11 (78%) were able to be a better patient educator. Others were able to contribute to improved patient outcomes and contribute more strongly in the health team (n=10; 71%). Reportedly, new knowledge and skills contributed to a change in others’ and self-perception (n=8; 57%). To be a leader and demonstrate influence were positively ranked by 50% of respondents although 64.2% were unsure whether they were better placed to gain a leadership position. In contrast to the increase in clinical skills, scholarly activities such as publication and presentation of new models of care were not considered achievable (Table 6).

Discussion

The reported study evaluated users’ learning experience, perceptions and outcomes from studying via online video learning activities. Significantly, respondents found that participation in the VLAs resulted in new knowledge/skills that resulted in improved self-efficacy and enabled them to provide better patient care and be a better patient educator. Consequently, this reportedly contributed to improved patient health outcomes and stronger contribution and influence in the multidisciplinary health team. The benefit of continuing professional education in improving competence has been identified [13]. Similar to findings from other studies of participants’ perception of CPE, participants generally perceived CPE as valuable and worthwhile and participated because it is mandatory and helps them to retain their jobs [14].

Generally, participants were shown to be experienced, busy professionals with a range of personal responsibilities. The majority of respondents lived in three Australian states and none were from overseas. Some respondents were born in countries other than Australia and spoke a variety of languages including Spanish, Mandarin, Hakka, Serbo-Croatian, Bosnian, Vietnamese, Tagalog and Afrikaans. VLAs were mainly preferred for their flexibility, availability; and personalised pace of studying. Participants were self-directed with studying and self-identified their study needs. Health professionals a positive attitude towards professional development is recognised [13].

The reported demographics of the study population show the aged care sector was the third most commonly reported area of employment and acute care the first. As stated in the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) report, in 2013, the work setting of employed nurses and midwives with the highest full time equivalent (FTE) rate was hospitals (excluding outpatients) (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2013).

The gender of the research participants reflects the gender proportions of the nursing and midwifery workforce in Australia. In 2013, 10.4% of nurses and midwives working in Australia identified as male (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2013), a similar proportion to those in the study (male 9.5%).

Participants in this study met the national Australian averages in relation to age, experience, gender and working hours. Similar to the respondents in this study (57.1%), data collected by the Australian Health Practitioner Registration Authority (AHPRA) in 2013 also shows that the majority of employed nurses and midwives (46.8%) work part time [15]. The desire for fulltime employment did not appear to be an incentive to study as the large majority (88.1%) of respondents indicated CPD was a re-registration requirement in Australia and consequently the primary reason for undertaking CPD. Disappointingly, the need for further education for promotion or other employment was not required, although this is not the case in some professions where CPEs become a valued credential that helps obtaining and keeping desirable positions, as well as advancement to the next level in careers [16].

Congruent with data collected by AHPRA in 2013 which shows that the majority of nurses were in the 50-54 year age bracket, followed by 55-59 years, and 45-49 years, the majority of respondents (61.4%) fell between the ages of 41 and 59 years (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2013). Ageing of the nursing workforce has been cited as a reason for the workforce shortages in nursing in Australia [15]. Accordingly, just under half of the respondents (42.8%) reported significant nursing/midwifery experience of over 30 years, ranging up to 50 years. Additionally, high responsibility levels including work plus study plus carer responsibilities may be a factor affecting nearly three quarters of the participants who reported not working fulltime.

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, in mid-2011 there was 27% of the total population born outside of Australia [1]. In accord, 31% of respondents were born outside Australia. This population consisted of people who were born in UK, NZ, Vietnam, India Philippines, Malaysia, El Salvador, Denmark, former Yugoslavia and South-Africa, showing Australia’s multi-culturism and therefore need to provide education that meets the needs of nurses and midwives educated outside Australia.

The major benefits of online learning are known to include convenience and increase accessibility to education. Respondents reported that Video Learning Activities were mainly preferred over classroom presentations for their flexibility, 24-hour availability, and personalised pace of study. Preference due to the currency of the material delivered was rated fifth of the nine options provided. Additionally, respondents living in a rural area indicated there was limited education available to them and the VLAs allowed nurses and midwives working in rural and remote areas to undertake CPD more readily and with greater flexibility. Geographic isolation and poor technological and telecommunications infrastructure and unemployment are identified as key barriers to CPE delivery and access [13,14].

The majority of respondents reported they had online learning experience with other education providers but rated the learning impact of VLAs higher. Respondents reported that their previous online learning experience had resulted significantly in a change in their knowledge and skills, a change in their self-confidence and change in their professional collaboration. This correlated with the outcomes of the VLAs where all respondents agreed/strongly agreed that participation in the VLA resulted in new knowledge/ skills and that with new knowledge they had increased confidence to advocate for best practice. Examination of the influence of interactive video on learning outcome and learner satisfaction in e-learning environments has shown that students in the e-learning environment that provided interactive video achieved significantly better learning performance and a higher level of learner satisfaction than those in other settings [5].

New knowledge and skills enables nurses to provide better patient care and be able to be a better patient educator, to contribute to improved patient outcomes and contribute more strongly in the health care team. Interestingly respondents were unsure they would be more able to influence healthcare, implement a new or changed model of care or present a new or changed model of care at a conference. Potentially, targeted education activities could address this lack of confidence or knowledge.

VLAs were considered to be desirable and beneficial to professional development. The majority of respondents did not prefer classroom teaching over VLAs. Augmented learning and self-assessment, increased knowledge and enhanced nursing skills were reportedly achieved from the VLAs. Most respondents found the learning useful and empowering (87.5%) and the VLAs allowed learners to identify what they have not learnt well (47.5%).

Limitations

The response rate to the study in general was lower than hoped and potentially limited the study and the sample size was too small to allow for meaningful statistics. The response rate in survey research is known to be problematical and a meaningful reward for participation such as CPD points may have increased participation. A larger sample with more diversity would have benefited our results as may have the inclusion of learners studying from international settings and experiencing different occurrences. Nevertheless, all respondents completed the questionnaire in enough detail for them to be analysed and contribute to answering the research questions and the low response rate does not appear to be impacted by non-response bias in a major way [17]. Due to the small number of participants data is not representative of all nurses and midwives.

For consistency and ability to compare and contrast data, using the AIHW style of requesting specific information for principal area of main job and work setting of main job reporting as basis for asking area of employment would have been beneficial. The majority of respondents lived in three of Australia’s eastern States and unknowingly the survey did not allow for overseas postcodes to be entered. A larger number of participants from rural areas of Central Australia and Western Australia and overseas may have provided different personal and professional demographics and a different reflection of needs and perspectives.

Conclusion

This descriptive research study was conducted as an internal service provision review and to determine the impact of CPD via online Video Learning Activities and the contribution made to learners’ professional practice. The study has contributed to the scarce literature about VLAs for CPD provided by private enterprise and to closing the gap in what is known about e-service usage for CPD by exploring learners’ experiences and learning outcomes of VLAs via online learning. The findings suggest that it may be important to integrate interactive instructional video into e-learning systems.

Participants generally perceived CPE as valuable and worthwhile and participated because it is mandatory and helps them to retain their jobs. A second main finding from this study is that nurses and midwives who undertook VLAs were confident they had gained new knowledge and skills, which could be applied to their practice. However, it is difficult to quantify or measure the direct impact of this new knowledge and skills on actual practice. This is because nurses and midwives may perceive they have applied their new knowledge and skills but this may not have translated into improved practice. Therefore, rather than only evaluate online learning per se, it is important that education providers evaluate the effectiveness in terms of knowledge transference to practice. In addition, providers need to ensure the technology used and the rigor of the education meets the needs of contemporary nurses and midwives.

The project trialled a methodology that may be applied by other education providers to assess the delivery of educational activities that improve learners’ self-efficacy, knowledge and translation of new knowledge and skills into practice. Challenges identified included gaps in rural education that could be met by e-learning and the need to continue to develop online learning opportunities. Education providers need to continue to provide topics that address the learning needs of nurses and midwives through a variety of strategies. Mitchell [18] insists that the values and beliefs following post registration education and practice decree that CPE must be tailored to the needs of the individual and relevant to the practice environment [18,19].

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (2013) Migration Australia, 2011-12 and 2012-13. Estimated resident population, Country of birth, State/ territory, Age and sex.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2013) Nursing and midwifery workforce

- Gikandi JW, Morrow D, Davis NE (2011) Online formative assessment in higher education: A review of the literature. Computers & Education 57(4): 2333-2351.

- Cobb SC (2004) Internet continuing education for health care professionals: An integrative review. J Contin Educ Health Prof 24(3): 171-180.

- Zhang D, Zhou L, Briggs RO, Nunamaker JF (2006) Instructional video in e-learning: Assessing the impact of interactive video on learning effectiveness. Information & management 43(1): 15-27.

- He Y, Swenson S, Lents N (2012) Online Video Tutorials Increase Learning of Difficult Concepts in an Undergraduate Analytical Chemistry Course. Journal of Chemical Education 89(9): 1128-1132.

- Engelland BT, Hopkins C, Workman L, Singh M (1998) Service quality and repeat usage: a case of rising expectations. Journal of Marketing Management 8(2): 1-6.

- Stark CM, Graham Kiefer ML, Devine CM, Dollahite JS, Olson CM (2011) Online Course Increases Nutrition Professionals’ Knowledge, Skills, and Self-Efficacy in Using an Ecological Approach to Prevent Childhood Obesity. J Nutr Educ Behav 43(5): 316-322.

- Ng KS, Abd R, Muhudin A (2014) E-Service Quality in Higher Education and Frequency of Use of the Service. International Education Studies 7(3): 1-10.

- Martin BA, Bruskiewitz RH, Chewning BA (2010) Effect of a tobacco cessation continuing professional education program on pharmacists’ confidence, skills, and practice-change behaviors. J Am Pharm Assoc 50(1): 9-16.

- Carlson J, OCass A (2010) Exploring the relationships between e-service quality, satisfaction, attitudes and behaviours in content-driven e-service web sites. The Journal of Services Marketing 24(2): 112-127.

- Pope C, Mays N, Popay J (2007) Synthesising Qualitative and Quantitative Health Research: A Guide to Methods. Maidenhead: Open University Press, UK.

- Keim KS, Gates GE, Johnson CA (2001) Dietetics professionals have a positive perception of professional development.J Am Diet Assoc 101(7): 820-824.

- Curran VR, Fleet L, Kirby F (2006) Factors influencing rural health care professionals’ access to continuing professional education. Aust J Rural Health 14(2): 51-55.

- Graham EM, Duffield C (2010) An ageing nursing workforce. Aust Health Rev 34(1): 44-48.

- Linney B J (1998) Why become a certified physician executive? Physician exec 24(2): 50-52.

- Rok Seon Choung, G Richard Locke III, Cathy D Schleck, Jeanette Y Ziegenfuss, Timothy J Beebe, Alan R Zinsmeister, et al. (2013) A low response rate does not necessarily indicate non-response bias n gastroenterology survey research: a population-based study. Journal of Public Health 21(1): 87-95.

- Mitchell M (1997) The continuing professional education needs of midwives. Nurse Educ Today 17(5): 394-402.

- Nsemo AD, John ME, Etifit RE, Mgbekem, MA, Oyira EJ (2013) Clinical nurses’ perception of continuing professional education as a tool for quality service delivery in public hospitals Calabar, Cross River State, Nigeria. Nurse Educ Pract 13(4): 328-334.

No comments:

Post a Comment