Theory of the Evolution of Multimorbidity: It is Created, In A Small Part but Significant, by the Medical Intervention Itself by Jose Luis Turabian in COJ Reviews & Research_Journal of Research and Review

Abstract

The morbidity evolution is uncertain. Not only in relation to the most obvious relationships, such as the evolution of bacterial resistance to antibiotics or genetic susceptibility to disease. Rather, this evolution of diseases over time and between countries is not explained in biologic changes but in contextual changes. And technological changes work to our advantage, but also to our detriment. There is a creation of new diseases, which result in giving pharmacological treatments for minor problems, increasing concern about future diseases in healthy populations, and converting personal and social problems into diagnosable health disorders and in need of pharmacological treatment. There is a medicalization of symptoms and risk factors. There is a recruitment of a greater number in diagnoses of chronic diseases through new detection and diagnosis technologies and the new disease definitions, as well as the equalization of risk factors with disease. It leads to overdiagnosis, over-treatment, multimorbidity and polypharmacy. This brings a dramatic increase in adverse drug reactions and drug-drug interactions. It is admitted that the mechanism due to causation, associations and links between diseases accounts for half of the reasons for accumulation of diseases, but the mechanism for iatrogenesis and complication accounts for another 10% of the causes of accumulation of diseases. Although it has long been known that the most important relationship on health is in psychosocial factors, current bio-technological evolution leads a new theory that complements the previous: multimorbidity and disease in general, in a small part but significant, can be created by the medical intervention itself. But it must bear in mind, that this mechanism could be prevented, so the presence of multimorbidity is not a natural and forced consequence of nature.

Keywords: Health care; Health expenditures; Drug-related side effects and adverse reactions; Overdiagnosis; Multimorbidity; Polypharmacy

Introduction

Biomedical development, especially focused on technology and drugs, has played a very important role in most of the fundamental advances in medicine, in the last 50 years. Scientific advances applied to health have increased people's survival. In addition, new medical technologies, interventions, innovative medical devices, advances in biochemistry, biomedical engineering and medical informatics, and medications for acute and chronic diseases are being developed and introduced with unprecedented speed, and it is virtually guaranteed, that science and engineering biomedical will be even more important in the future [1,2].

However, there are dark parts in those bright perspectives. There is an epidemic of diagnoses and treatments. The prevalence of the disease is growing rapidly in societies with high-tech medicine. On the other hand, the feeling of being sick grows while global health seems to improve dramatically. The feeling of being sick is greater the better the objective data, such as life expectancy [3,4].

The morbidity evolution is uncertain. Not only in relation to the most obvious relationships such as the evolution of bacterial resistance to antibiotics or genetic susceptibility to disease. Rather, this evolution of diseases over time and between countries is not explained in genetic changes but in contextual changes, and technological changes work to our advantage, but also to our detriment.

In this way, there is a creation of new diseases, which result in giving pharmacological treatments for minor problems, increasing concern about future diseases in healthy populations, and converting personal and social problems into diagnosable health disorders and in need of pharmacological treatment [5].

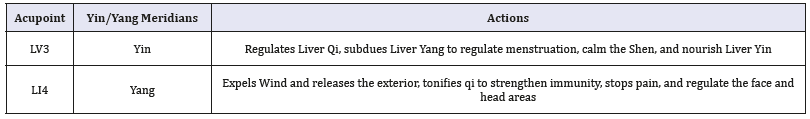

Many processes that were previously foreign to medicine have been explained and treated by doctors. The recruitment of a greater number in diagnoses of chronic diseases through new detection and diagnosis technologies and the disease definitions, as well as the equalization of risk factors with disease, leads to overdiagnosis, over-treatment, multimorbidity and polypharmacy. There is a medicalization of symptoms and risk factors, such as in the pre-diabetes, where a war against "prediabetes" has created millions of new patients and a tempting opportunity for the pharmaceutical industry [6], or as the increasing criteria of primary prevention treatments for cardiovascular diseases with statins, according to which the number of people susceptible to treatment increases between 30-60% [7].

On the other hand, high-risk prevention strategies have the disadvantage of their inability to prevent diseases in a large part of the population with a relatively small average risk and where most cases of disease originate. Expanding the criteria that justify individual preventive interventions lead to the treatment of larger and healthier strata of the population [8].

All these phenomena, which are rooted in current biomedical practice, bring with it the increase in multimorbidity. Multimorbility is the presence of two or more long-term conditions, with the overlapping of mental, cardiovascular, diabetes, cancer and respiratory diseases. Multimorbidity is now a generalized phenomenon that affects the health of populations throughout the world, with the highest burden among individuals or disadvantaged subpopulations, having become a serious public health problem due to its negative consequences on the quality of life, the greater tendency to disability and mortality, polypharmacy, and cost of utilization of health services, and that give place to a considerable burden of care. Multimorbidity is not simply a problem of chronological ageing, neither it is randomly distributed [9,10].

The increase in multimorbidity and polypharmacy brings with it a dramatic increase in adverse drug reactions and drug-drug interactions. Cascade prescription occurs when a new drug is prescribed to "treat" an adverse reaction caused by another drug, based on the mistaken belief that a new medical condition has developed.

Adverse events associated with cascade prescription occur when the second drug increases the severity of the adverse reaction produced by the first drug, or when the second drug exposes the patient to the occurrence of new adverse reactions. Of every 100 courses of drug treatment, there are 20 adverse drug reactions, between 5 and 25 of clinically observable drug-drug interactions and between 15 and 50 potential drug-drug interactions, which arrive to 100 in geriatric patients [11-13].

It has been found that the application of individual disease guidelines in a patient with five chronic conditions would result in the prescription of 19 doses of 12 different medications, taken at five time points during the day, and that carries the risk of 10 concomitant interactions or adverse events. Care that is "significantly better" can be significantly worse and a nightmare for the patient [14].

The study of the natural history of the accumulation of diseases in patients, proposes a new theory: multimorbidity, in a small but significant part, is created by the medical intervention itself. It is admitted that the mechanism due to causation, associations and links between diseases accounts for more than half of the reasons for accumulation of diseases, and the mechanism for iatrogenesis and complication accounts for another 10% of the causes of accumulation of diseases.

And we must bear in mind that both mechanisms could be prevented, so the presence of multimorbidity is not a natural and forced consequence of nature. The accumulation of health problems in people can be prevented, on the one hand, by acting on causation mechanisms, associations and links between diseases, which occur in the initial stages of pathological processes, but mainly by avoiding iatrogenesis and complication, which occurs in the final phase of pathobiography, which could eliminate more than 10% of the accumulated health problems in patients with multimorbidity [15].

It should be clear that the increase in health demand, the frequency of patient visits to the doctor's office, the increase in morbidity and multimorbidity, and the feeling of "discomfort" in people despite reducing mortality, cannot be resolved by increase in the supply of resources, nor with the increase in biomedical interventions and pharmacological treatments, but on the contrary, the organizational characteristics of the biomedical practice and the biomedical technical actions are causes, not negligible, of the inefficiency, increase of the health demand, increased costs and iatrogenesis.

It is the existing trends of medicalization that increase the prevalence of the disease and its treatment giving rise to polytherapy with its consequences of disease that theoretically requires more pharmacological interventions and consequently more disease, etc. This catastrophic loop occurs, for example, when drug treatment, from the beginning, is carried out with associations of medications, with the use of higher doses of medications, and/or with detection and preventive advice that are not based on scientific evidence, etc.

Although it has long been known that the most important relationship on health is in psychosocial factors [16], a new theory on the accumulation of diseases and the creation of multimorbidity and net disease is proposed: multimorbidity and disease in general, in a small part but significant, can be created by the medical intervention itself.

References

- Turabian JL (2017) Metaphors to think about technological tools and patients care in family medicine. Res Med Eng Sc 2(4).

- Turabian JL (2018) Medical advancements associated with biomedical science must be so slender, as powerful, and as serene as a gothic cathedral. Br Biomed Bull 6(1): e309.

- Sen A (2002) Health: Perception versus observation. BMJ 324(7342): 860-861.

- Illich I (2017) The obsession with perfect health. Journal for Cultural Research 21(3): 286-291.

- Moynihan R, Brodersen J, Heath I, Johansson M, Kuehlein T, et al. (2019) Reforming disease definitions: A new primary care led, people-centred approach. BMJ Evid Based Med 24(5):170-173.

- Piller C (2019) Dubious diagnosis. Science 363(6431): 1026-1031.

- Fort A (2018) How do I use the new cholesterol guidelines? Clinician Reviews 28(10): 18-19.

- Chiolero A, Paradis G, Paccaud F (2015) The pseudo-high-risk prevention strategy. Int J Epidemiol 44(5): 1469-1473.

- Turabian JL, Perez FB (2016) A way of helping “Mr. Minotaur” and “Ms. Ariadne” to exit from the multiple morbidity labyrinth: The “Master Problems”. Semergen 42: 38-48.

- Turabian JL (2018) Notes for a theory of multimorbidity in general medicine: The problem of multimorbidity care is not in practice, but in the lack of theoretical conceptualization. Journal of Public Health and General Medicine 1(1): 1-7.

- Hennessy S, Flockhart DA (2012) The need for translational research on drug-drug interactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther 91(5): 71-73.

- Kolchinsky A, Lourenço A, Li L, Rocha LM (2013) Evaluation of linear classifiers on articles containing pharmacokinetic evidence of drug-drug interactions. Pac Symp Biocomput pp.409-420.

- Turabian JL (2019) Approach to the epidemiology of drug interactions in primary health care. The visible part of a dangerous great iceberg growing rapidly. Epidemol Int J 3(2): 000126.

- Mangin D (2012) Beyond diagnosis: Rising to the multimorbidity challenge. BMJ 344: e3526.

- Turabian JL (2018) Longitudinal study of a series of cases on trajectory of the chain of accumulating health problems in certain people. Am J Family Med 1(1): 1001.

- Wilkinson R (2000) Mind the gap-hierarchies, health and human evolution. London, UK.