The Peaceful Transition of Jebus into Ir David (Jerusalem) and the Location of the Tent of Congregation by Zeev Lewy in Archaeology & Anthropology:Open Access_journal of Anthropology

Abstract

Geological (sedimentological) aspects evaluating the excavation of Jebus suggest that the Jebusites worshipped God of Nature. It did not threaten the Jewish monotheistic belief compared to the religious ritual and habits of the other Canaanites, for which the city of Jebus existed until David captured it without any bloodshed or destruction. Lithological affinities substantiate the biblical records of the early constructions in David’s City (Ir David; southeast Jerusalem) such as the Millo and the location of the Tent of Congregation housing the Ark of the Covenant until the temple was built and inaugurated by King Solomon.

Keywords: City of Jebus (Salem); Jebusites atheists; Jebus became King David’s capital (Ir David); Biblical and geological aspects; Tent of Congregation in Ir David (East Jerusalem)

Introduction

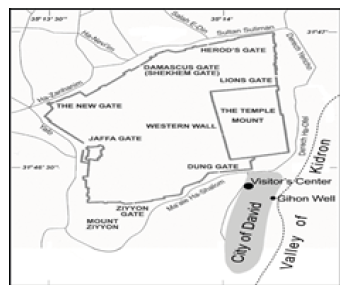

Intensive excavations were carried out by several archaeologists southeast of the old city of Jerusalem on the ridge where relics of the city of Jebus and the Israeli City of David (Figure 1) were unearthed. These excavations were restricted to limited sites in between inhabited areas affecting the evaluation of the overall historical record and raising methodical conflicts of dating of the archaeological findings and their assumed identity and function [1]. In 2005 Eilat Mazar returned to the site that was partly unearthed by Macalister & Duncan [2] at the northeastern part of the ridge of the city of David (Hill of Ophel) underlying the Visitor’s Center (Figure 1). In 2006 she invited Aryeh Shimron and me to observe in the eyes of geologists a 4-6cm thick horizontal layer of crushed white limestone (White Layer). Its sedimentological and petrographic affinities provided interesting insights on the religious belief of the Jebusites, their relationships with the Israelites, and the early stages of Jebus turning into Ir David, the capital of David’s Kingdom. Most surprising was the identification of the location of the tent of congregation which served the nation for about forty years until the inauguration of the First Temple on Mount Moriah.

Figure 1:Excavation site in Ir David (City of David) at the visitor’s center in Southeast Jerusalem.

The white layer

The White Layer overlies a wedge of soil with stones and pottery sherds covering the inclined bedrock. This bedrock consists of white limestone of the upper part of the Bina Formation (Late Turonian age, about 88 million years before present). It is situated on the eastern flank of the Judean anticlinorium gently inclining eastwards where the Turonian limestone is overlain by soft white chalk of the younger Menuha Formation. The upper few millimeters of the finely crystallized (micrite) white limestone bedrock altered by microbial (endolithic algae) and chemical processes into ‘nari’, consisting of tiny spherules in a fine-grained calcareous matrix. It is covered by a gray patina with a few grains of iron-oxide probably as the result of frequent wetting and precipitation of dissolved component on the surface through evaporation. Rectangular shallow grooves about 20cm long and 7-10cm wide (Figure 2) and larger elliptical pits about 60cm long and 30-35cm wide (Figure 3) are scattered over the surface. These Chalcolithic (4000-2200 years BCE) stationary grinding installations (cupmarks) cut by men into the rock were first uncovered by Macalister & Duncan [2] and further traced on the bedrock surface by Mazar [3]. They were mentioned and illustrated in the comprehensive study of these rock-cut facilities in Israel [4,5]. The inner side of the cupmarks is covered by the same weathering patina as the bed-rock surface indicating the long exposure of these unused grinding structures to weathering like the whole surface.

Figure 2:Rectangular (20x7-10cm) stationary grinding facilities (cupmarks) cut into the bedrock of Ir-David (photo by the courtesy of Shimron A).

Figure 3:Elliptical cupmarks (50 x 35-30 cm) cut into the bedrock.

The monotheistic jebusites did not threaten the Israelites

This exposed stretch of rock surface between the eastern part of the wall of the city of Jebus (Salem=Shalem) and the steep escarp into the Valley of Kidron (Figure 1) must have had a significant function in the life of the Jebusites, for which it remained unbuilt, perhaps for religious ritual purposes [6]. The unused grinding facilities must have been filled with rain water, which attracted birds and animals. This indirect support of wild life might have become part of a worship of God of Nature whereby drinking water was supplied throughout the whole year from the Gihon Well (Figure 1) under the city. The deduced monotheistic belief of the Jebusites is referred to in the Bible describing Melchizedek one of the early kings of Jebus (Salem=Jerusalem) as “priest of God Most High” who blessed Abraham “by God Most High, creator of heaven and earth” (Genesis 14: 18-19). The monotheistic belief of the Canaanite Jebusites may explain why they survived the eradication of the other kingdoms during the conquest of Canaan by the Israelites. The Bible lists the names of the kings who were defeated and their occupied cities, among them the Jebusites (Joshua 12:8). However, this compilation was corrected by admitting that “at Jerusalem, the men of Judah were unable to drive out the Jebusites who lived there, and to this day Jebusites and men of Judah lived together in Jerusalem” (Joshua 15:63). Since Jebus was situated between the territories of Judah and Benjamin, the latter tribe was blamed as well of letting the Jebusites to stay in their city: ”But the Benjamites did not drive out the Jebusites of Jerusalem; and the Jebusites have lived on in Jerusalem with the Benjamites till the present day” (Judges 1:21).

The accusation of both neighboring tribes of being unable to carry out their duty to clear Canaan from all pagan gentiles does not seem to blame their military inability by which they took over their territories. It seems that both tribes did not find it necessary to expel the Jebusites from their city, which provided a topographic barrier between their territories, especially since the citizens were probably friendly and enabled free crossing of this central route junction. The unification of the twelve Israeli tribes within a kingdom required to take over Jebus controlling the road junction and establish there the capital of the Israeli Kingdom. The friendly occupation of the city of Jebus and the assimilation of its inhabitants without any bloodshed and destructions (“Joab repaired the rest of the city”; 1 Chronicles 11:8) seems logical in light of the concluded monotheistic belief of the Jebusites and their friendly relationships with the Israelites, which continued after King David captured the city. Despite taking over the whole region David insisted to pay the defeated Jebusite king Arunah for his threshing-floor to build an altar to the Lord (2 Samuel 24:21) saying: “ I will not offer to the Lord my God whole-offerings that have cost me nothing” (2 Samuel 24:24).

The location of the tent of congregation in king David’s capital (Ir David)

The Jebusite unbuilt ritualistic area provided excellent sites for rapid building of the main institutions and houses of the monarchy, avoiding the destruction of Jebusite constructions. Building on this eastward inclined undulating area required to level the surface. This was done by a cover and fill of soil mixed with rock fragments and pottery sherds dominated by Iron Age I pottery (12th-11th century BCE [6] thickening eastward (Figure 4). It is reasonable to assume that most, or all of these sherds comprised old Jebusite waist, which became useful for the foundation of the Israeli City of David but were controversial for dating the fill. The leveled surface was covered by 4-6cm thick layer of crashed white limestone (White Layer; (Figure 4) of the same bedrock of the Jebusite ritual area comprising fragments of the weathered (‘nari’) rock-type. The friable nature of the White Layer neither stabilized the underlying friable fill, nor the constructions on top of it. Therefore, the White Layer must have had another non-constructional purpose. The above deduced monotheistic belief of the Jebusites who worshipped the God of Nature explains the significance of the White Layer as a physical and spiritual divided between two religious entities.

Figure 4:The horizontal thin White Layer on top of the bedrock (to the left) and on the eastward (to the right) thickening fill of soil mixed with rock fragments and pottery sherds (photo by the courtesy of Shimron A).

The bedrock surface and the cupmarks below the visitor’s center were not quarried to level the surface for the new constructions, though such levelling of the bedrock was observed in other sites. The white layer was observed at the Visitor’s Center excavation site (Figure 1) only. It expresses purity and was probably believed to seal the underlying spirit of the Jebusite religious ritual. Such a religious influence would not affect regular buildings like the palace of King David that was probably discovered in this site [6]. However, the holiness of an Israeli religious construction might be affected when in direct contact with the Jebusite religious ritual surface. It is suggested that the White Layer formed the basis for the temporary site of the Tent of Congregation housing the Ark of Convention as recorded that “David built himself quarters in the City of David, and prepared a place for the Ark of God and pitched a tent for it” (1 Chronicles 15:1), a place which King David “had prepared for it, for he had pitched a tent for it in Jerusalem” (2 Chronicles 1:4). The Tent of Congregation operated in the City of David for nearly forty-four years (David was king of Jerusalem 33 years; 1 Kings 2:11) until King Solomon built the First Temple (inaugurated at about 956 B.C.E.). This site had the most impressive view, as well as physical protection by the escarp to the east into the Valley of Kidron (Figure 1).

The stepped wall (Millo) supporting the construction of the City of David

Mazar [6] unearthed part of the large-stone structure previously excavated by Macalister & Duncan [2], which they interpreted as ruins of a Jebusite wall destroyed by King David. Its blocks overlay in places the soil fill on top the southeastward inclined bedrock comprising impressive quantities of badly worn Iron Age I pottery sherd dating the large-stone structure as of late Iron Age I or early Iron Age IIa around 1000 BCE [6]. The Large-stone structure situated close to the escarp of the Kidron Valley was built on a rather thick friable fill that had to be stabilized by a supporting wall along the escarp edge. However, such a wall would be pushed over the edge by the load of the buildings and the swelling of the argillaceous fill by rainwater. Mazar [6] realized that a stabilizing wall had to be situated on firm ground to avoid the eastward collapse of the whole construction site. Relics of such a supporting wall occur on the escarp as a stepped stone wall (Figure 5) consisting of stepwise layered limestone blocks leaning on the inclined escarp. Mazar [6] suggested that this Stepped-Stone Structure probably reached the top of the escarpment in order to support the friable artificial platform, on top of which stood the large-stone structure, which might be part of King David’s palace. Therefore, both impressive structures belong to the same constructional phase [3]. The Bible informs that “David did capture the stronghold of Zion, and it is now known as the city pf David” (2 Samuel 5:7). This stronghold was interpreted as a fortress defending Jebus on the edge of the escarp into the Kidron Valley where it would be supported by the stepped-stone structure [7,8]. However, David occupied the fortified city of Jebus (“stronghold of Zion”) which he named Ir David and built around it (2 Samuel 5:9). “Analysis of both the stratigraphic and ceramic evidence suggests that the stepped rampart was built during the transition from the Late Bronze Age II to the Iron Age I” [9], which includes King David’s period. This wide range of dating is explained by the incorporation of old pottery sherds in the fill behind the stone wall.

Figure 5:Part of the stepped-stone structure (Millo), which ranged upwards to stabilize the friable fill on which the early constructions of the city of David were situated.

The logical constructional succession [6] suggests that at first the Stepped-Stone Structure was erected in order to stabilize the friable fill, on which the Large-Stone Structure and other buildings were erected by the masons of King David. The herein reconstructed religious ritual of the Jebusites worshipping God of Nature by supplying drinking water to wildlife substantiates the constructional scenario [6]. As long as the Jebusite’s ritual continued the water flow toward the Kidron Valley prevented any building of Ir David. The biblical record on the early stages of the construction of King David’s capital tells that: “David took up his residence in the stronghold and called it the City of David. He built the city round it, starting at the Millo and working inwards” (2 Samuel 5:9). The biblical term Millo originates from the Hebrew name Milui meaning fill, which levelled the unbuilt area prepared for the constructions of the capital of the kingdom outside the city of Jebus. The levelling friable fill was stabilized by the uppermost part of the stepped wall. “Starting at the Millo and working inward” seems to refer to the external stepped wall stabilizing the fill (milui), hence the name of the wall Millo, that King David started to build at about 1000BCE. (occupation of Jebus dated to 1004BCE) and was completed by King Solomon.

Acknowledgment

I thank Prof. E. Mazar for permitting me to extend her research on Ir David. Dr. Aryeh Shimron provided me with two pictures of sites in Ir David, which are not preserved anymore.

References

- Maeir AM (2017) Assessing Jerusalem in the middle bronze age: A 2017 perspective. In: Gadot Y, Silverman CK, Uziel J (Eds.), New studies in the archaeology of Jerusalem and its region. Jerusalem, Israel, 11: 64-74.

- Macalister RAS, Duncan JG (1926) Excavations on the hill of Ophel, Jerusalem, 1923-1925. Palestine Exploration Funds, Annual IV, London, United Kingdom.

- Mazar E (2007) Preliminary report on the city of david excavations (2005) at the visitor’s center area. Jerusalem, Israel.

- Brink Vanden ECM (2008) A new fossile directeur of the chalcolithic landscape in the shephelah and the samarian and judean hill countries: Stationary grinding facilities in bedrock. IEJ 58(1): 1-23.

- Eitam D (2009) Cereals in the thessalian culture in central Israel: Grinding installations as a case study. Israel Exploration Journal 59: 63- 79.

- Mazar E (2006) Did I find king David’s palace? Biblical Archaeology Review 32: 16-27.

- Kenyon KM (1974) Digging up Jerusalem. New York, USA.

- Cahill JM (2004) Jerusalem in David and Solomon’s time. Biblical Archaeological Review 30(6): 20-31.

- Cahill JM (2003) Jerusalem at the time of the united monarchy: The archaeological evidence. In: Vaughn AG, Killebrew AE (Eds.), Jerusalem in bible and archaeology. The First temple period. Society of Biblical Literature, Atlanta, Georgia, pp. 12-80.

No comments:

Post a Comment