Sevelamer-Induced Esophagitis: A Rare Cause of Severe Gastrointestinal Injury by Khurram J Khan in Gastroenterology Medicine & Research_Gastroenterology Open Access Articles

Abstract

Sevelamer is a noncalcium-containing phosphate binding medication recommended in guidelines for treatment of hyperphosphatemia in kidney disease. Common gastrointestinal side-effects include abdominal pain, dyspepsia, and vomiting, but gastrointestinal bleeding is not a recognized side effect of sevelamer. The first reported case of sevelamer-induced gastrointestinal injury was in 2013, and since then, very few cases have been described in the literature and the majority of those cases describe lower gastrointestinal bleeding. We report a case of hemodynamically significant sevelamer-induced bleeding from severe esophagitis confirmed with biopsy.

In September 2018, a 79-year-old comorbid female presented with an acute decrease in hemoglobin of 40g/L and a one day history of melena stools with a significant drop in her blood pressure. After reversal of her warfarin induced coagulopathy, an urgent endoscopy demonstrated severe circumferential esophagitis. Biopsies were taken to rule out infectious etiologies, and she was treated with PPI infusion and stabilized. Pathology confirmed the presence of “fish scale” crystals that are magenta on Ziehl-Neelsen staining, violet on periodic acid-Schiff-diastase staining, and golden brown on Gomora methenamine silver staining, which are characteristic of sevelamer crystals. A diagnosis of sevelamer-induced esophagitis was made. The patient improved with cessation of sevelamer without further related complications.

Conclusion: Sevelamer is a rare cause of significant upper gastrointestinal injury and can be confirmed on biopsy if suspected. Sevelamer may be underappreciated as a cause of occult gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with chronic kidney disease or anti-coagulation. This case highlights the necessity of further research to elucidate the true incidence of sevelamer-induced gastrointestinal injury, and the risk factors that predispose patients to developing this complication.

Keywords: Esophagitis; Drug-induced; Pathology

Abbreviations: KDIGO: Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes; AVA: Aortic Valve Area; AFB: AcidFast Bacilli; MRSA: Methicillin Resistant S Aureus

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a common health ailment with an estimated prevalence of up to 2.9million Canadians [1]. Hyperphosphatemia is a well-known complication of CKD that significantly increases the risk of vascular calcification and cardiovascular mortality [2]. Sevelamer is a phosphate binding medication that was shown in 2002 to slow the progression of vascular calcification in patients with CKD [3]. Sevelamer was also recently recommended in the KDIGO 2017 Clinical Practice Guideline Update for use in patients with chronic kidney disease [4]. The treatment of hyperphosphatemia in patients with CKD can be administered through calcium-containing or noncalcium-containing phosphate binders. Common calcium-containing binders include calcium carbonate and calcium acetate, while noncalcium- containing binders include sevelamer and lanthanum. In general, noncalcium-containing binders are preferred as it has been associated with lower mortality and significantly lower hospitalization rates [5].

The first description of sevelamer-induced gastrointestinal injury (SIGI) was published in 2013, where seven patient cases were reported [6]. Only two cases involved injury to the esophagus. A third case was published in 2014, where severe esophagitis with histopathological evidence suggestive of sevelamer-induced esophagitis (SIE) was found [7]. A review of the case reports regarding SIGI published from 2013 to 2017 found that 16 cases of SIGI have been reported in that time, and 81% of cases presented with intestinal involvement [8].

SIGI is a rare clinical entity that has been only recently described in the literature. It is still less common for SIGI to manifest with upper gastrointestinal bleeding, and esophageal involvement. We describe a case of severe circumferential esophagitis secondary to sevelamer use presenting with upper gastrointestinal bleeding in a 79-year-old female with chronic kidney disease.

Case Presentation

A 79 year old female presents to hospital with a past medical history of end-stage-renal-disease secondary to type 2 diabetes requiring intermittent hemodialysis for six years, a remote history of peptic ulcer disease in 1990, atrial fibrillation with a CHADS2 score of 3, hypertension, dyslipidemia, moderate aortic stenosis (echocardiogram 10 months ago showed AVA 0.82, LVEF 61%, and no wall motion abnormality), osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia, depression, and peripheral vascular disease. She has a remote history of cholecystectomy, appendectomy, bilateral total knee arthroplasty complicated by pulmonary embolism several years ago, shoulder arthroplasty, and bilateral total hip arthroplasty. She had recently been diagnosed with a left foot cellulitis, and treatment was ongoing with ciprofloxacin and cefazolin. She had received these antibiotics for 1 week prior to admission. She presents to hospital with a 48hour history of 6-8 loose watery non-bloody bowel movements daily, followed by a 24hour history of five occurrences of melena stool and decreased level of consciousness from baseline. Her vital signs on admission include blood pressure 97/65, pulse 91, temperature 36.5 degrees Celsius, and respiratory rate 16. Her blood pressure acutely decreased to 70/50, and she was found to have confusion and significant drowsiness at this time. Her blood pressure returned to 102/58 and cognitive status returned to baseline with normal saline 500mL IV. A CT head without contrast showed no acute abnormality. Given her labile blood pressure and fluctuating cognition, she was admitted to a monitored ward.

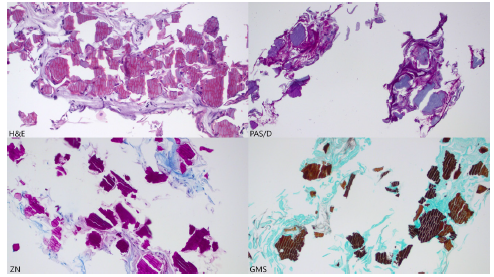

Her hemoglobin 5 days prior to admission was 103g/L, which was found to be 61g/L on admission. She was transfused two units of fresh frozen plasma, and two units of packed red blood cells; her hemoglobin one hour after the transfusion was 99g/L. Her prothrombin time was 5.6 in the absence of oral anticoagulation therapy. She received one dose of vitamin K 10mg IV and her prothrombin time decreased to 1.4 in 24 hours. An esophagogastroduodenoscopy was performed within 12 hours of admission, which showed severe circumferential esophagitis in the distal esophagus without active bleeding, in addition to a small superficial ulcer in the anterior duodenal bulb. Two biopsies were taken which demonstrated esophageal mucosal injury and crystals of Sevelamer. Sections demonstrated two-toned crystals with bright pink linear accentuations and a rusty yellow background. The crystals are magenta on ZN (AFB) staining, violet on PAS/D staining, and golden brown on GMS staining with internal demarcations (fish scales) (Figure 1). Her hemoglobin stabilized after initiation of intravenous pantoprazole 80mg IV bolus followed by 8mg/hour infusion.

Figure 1:Pathology staining.

She was also investigated for suspected osteomyelitis of her left foot and was transitioned to piperacillin/tazobactam and vancomycin on admission. She had undergone evaluation 2 days before admission for suspected critical limb ischemia of the left lower extremity, with plan for angiography and potential angioplasty. The angiography was performed 48hours after her hemoglobin stabilized, and recanalization of the left popliteal and proximal anterior tibial arteries was performed successfully. She had a bone scan one week after admission that showed hyperemia and active osteoblastic turnover in the left foot. Bone to probe testing was positive, and superficial wound swabs were positive for MRSA. She was continued on piperacillin/tazobactam and vancomycin with wound care. Ongoing pain control for her suspected osteomyelitis and arthritis led to fluctuating levels of consciousness and type 2 respiratory failure. The patient’s family decided to transition to palliative care to achieve adequate pain control. The patient passed away the following week.

Discussion

Sevelamer is a commonly prescribed phosphate binding medication in patients with chronic kidney disease. SIE is a rare diagnosis that has seldom been described in the literature. This presents a diagnostic challenge for gastroenterologists and pathologists in making the diagnosis. Several gastrointestinal side effects, including dyspepsia, abdominal pain, vomiting, and diarrhea, have been listed on the sevelamer product monograph [9], but mechanical gastrointestinal injury has not been investigated or reported. There are three major types of resins that can cause mechanical injury to gastrointestinal and respiratory mucosa. These include sevelamer, kayexalate, and cholestyramine [10]. Each of these three resins has distinct histopathological characteristics that aid in differentiating them from each other. For example, while kayexalate and cholestyramine both exhibit fish scale patterns on microscopy, the former will stain purple under H&E staining while the latter will stain pink. It is important for clinicians to remain wary of these two sevelamer mimics that can cause similar gastrointestinal injury, or respiratory injury if the patient has aspirated gastric contents.

A common alternative noncalcium-containing phosphate binder is lanthanum. A systematic review and meta-analysis published in 2017 compared the safety and efficacy of sevelamer with lanthanum and other iron-based binders. There was no statistically significant difference in mortality or hospitalization rates between sevelamer and lanthanum use [11]. In 2015, the first reported case of lanthanum-induced gastrointestinal histiocytosis was described [12]. Two years later, five more cases of lanthanum related histiocytic deposits in the gastrointestinal mucosa leading to gastrointestinal injury were reported [13]. Overall, it remains unclear if lanthanum carries a lower risk of gastrointestinal injury than sevelamer. However, lanthanum has been found to be a more cost-effective option than sevelamer, with similar phosphate lowering efficacy [14,15]. As there have been very few cases of SIGI in the literature, it is difficult to identify risk factors that predispose patients to this disease. The most recent review of the known cases of SIGI found that there was a high prevalence of co-morbid diabetes in patients who developed SIGI8.

This case demonstrates that sevelamer can be a cause of hemodynamically significant gastrointestinal injury and bleeding. There have been very few cases of SIGI published in the literature, and even fewer cases of SIE. Clinicians must consider sevelamer as a cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with chronic kidney disease and should promptly discontinue sevelamer if the diagnosis is confirmed. SIE may also be a cause of occult gastrointestinal blood loss in patients with CKD. Lanthanum carbonate may be a viable alternative for patients who develop SIGI, but there is a risk of gastrointestinal histiocytosis. Further research to identify the incidence of SIE and the co-morbidities that increase the risk of developing SIE is warranted.

Acknowledgment

This case report was presented as a poster at the Canadian Digestive Diseases Week Meeting in February 2019 at Banff, Canada.

Conflicts of Interest

None of the authors have conflicts of interests to disclose.

References

- Stigant C, Stevens L, Levin A (2003) Nephrology: Strategies for the care of adults with chronic kidney disease. CMAJ 168(12): 1553–1560.

- Shaman A, Kowalski S (2016) Hyperphosphatemia management in patients with chronic kidney disease. Saudi Pharm J 24(4): 494-505.

- Chertow G, Burke S, Raggi P (2002) Sevelamer attenuates the progression of coronary and aortic calcification in hemodialysis patients. Clinical Nephrology 62(1): 245-252.

- KDIGO 2017 Clinical practice guideline update for the diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD). Kidney Int Suppl 7(1): 29-31.

- Jamal S, Vandermeer R, Mendelssohn D (2013) Effect of calcium-based versus non-calcium-based phosphate binders on mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 382(9900): 1268-1277.

- Swanson BJ, Limketkai BN, Liu TC, Montgomery E, Nazari K, et al. (2013) Sevelamer crystals in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT): A new entity associated with mucosal injury. Am J Surg Pathol 37(11): 1686-1693.

- Moran A, Franz F, Hoops T (2014) Sevelamer crystals in patient with severe erosive esophagitis and multiple superficial ulcerations in the duodenum. Am J Surg Pathol 142(1): A271.

- Yuste C, Mérida E, Hernández E, García Santiago A, Rodríguez Y, et al. (2017) Gastrointestinal complications induced by sevelamer crystals. Clin Kidney J 10(4): 539-544.

- (2017) Renagel (sevelamer hydrochloride) (product monograph). Sanofi-Aventis, Laval, Quebec, Canada.

- Gonzalez R, Lagana S, Szeto O (2017) Challenges in diagnosic medication resins in surgical pathology specimens. Arch Pathol Lab Med 141(9): 1276-1282.

- Habbous S, Przech S, Acedillo R, Sarma S, Garg AX, et al. (2017) The efficacy and safety of sevelamer and lanthanum versus calcium-containing and iron-based binders in treating hyperphosphatemia in patients with chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 32(1): 111-125.

- Rothenberg M, Araya H, Longacre T (2015) Lanthanum-induced gastrointestinal histiocytosis. ACG Case Rep J 2(3): 187-189.

- Hoda R, Sanyal S, Abraham J (2017) Lanthanum deposition from oral lanthanum carbonate in the upper gastrointestinal tract. Histopathology 70(7): 1072-1078.

- Park H, Rascati KL, Keith MS, Hodgkins P, Smyth M, et al. (2011) Cost-effectiveness of lanthanum carbonate versus sevelamer hydrochloride for the treatment of hyperphosphatemia in patients with end-stage renal disease: A US Payer Perspective. Value in Health 14(8): 1002-1009.

- Robison R, Cooney D, Low M (2016) Sevelamer carbonate and lanthanum usage evaluation and cost considerations at a veteran’s affairs medical center. Hosp Pharm 51(4): 312-319.

No comments:

Post a Comment